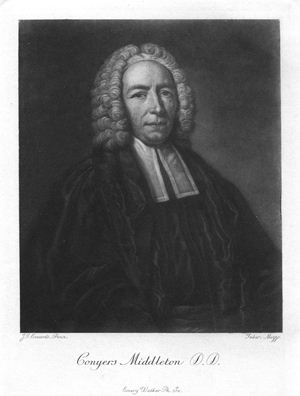

Conyers Middleton

1683-1750. University Librarian; principal opponent of Bentley.

Educated at the cathedral school at York, Conyers Middleton was admitted pensioner at Trinity College, Cambridge, on 18 March 1699. Named scholar in 1701, he graduated BA in 1703 and proceeded MA in 1706, having been elected a Fellow n 1705. He was ordained deacon in 1707 and priest in 1708. Though disappointed in not receiving the preferments that he had expected Middleton held a number of clerical appointments: he was Rector of St Saviour's, Norwich (1719), St Clement's-at-Bridge, Norwich (1720-25), of Coveney, Cambridgeshire (1725-8), and of Hascombe, Surrey, from 1747 to his death. Except possibly at Coveney he was non-resident.

As a young man, being very fat and suffering from a nervous disorder in his face, Middleton resorted to a severe dietary regimen that left him thin and in delicate health. An intimate friend, the antiquarian William Cole, observed that he was:

a most regular and temperate man; never spent an evening from home, never touched a drop of wine, or anything that was salt, or high seasoned; but was one of the most sober, well-bred, easy and companionable men I ever conversed with. (Walpole, Corr., 308)

Though Middleton did meet friends at a coffee house in the evenings he otherwise spent most of his time at home. Except while travelling he was always seen dressed in his gown and cassock, and regularly attended St Michael's Church, Cambridge, with his family. Furthermore, according to Cole his conversation never hinted of any irreverence toward religion or the established church. Appearances notwithstanding, in 1734 he confessed to Lord Hervey:

Sunday is my only day of rest, but not of liberty; for I am bound to a double attendance at church, to wipe off the stain of infidelity. When I have recovered my credit, in which I make daily progress, I may use more freedom. (Chalmers, 145)

He ‘was immoderately fond of music, and was himself a performer on the violin’ (Walpole, Corr., 310); this avocation earned him the contempt of his nemesis at Cambridge, Richard Bentley, who derided him for being ‘a fiddler’ rather than a scholar.

Though he died childless Middleton was married three times; he was a devoted husband to all his wives and was laid to rest with them in his church at Cambridge. His first wife Sarah Drake brought Middleton a handsome fortune, which enabled him to quit his fellowship at Trinity and dwell in a fine house in the best part of town. His third wife, Anne Wilkins was a gifted harpsichordist who regularly performed in concert with her husband and his niece at their home.

Throughout most of his life at Cambridge, Middleton was a valiant combatant in the bitter war fought against the tyrannical master of Trinity, Richard Bentley. Upon assuming power in 1700 Bentley, the friend and admirer of Isaac Newton, was ambitious to reform his College after what has been described as ‘the most calamitous decline in the history of the university’ during the politically turbulent seventeenth century, and to promote research, especially in the physical sciences. But his open contempt of the Fellows brought him into continual turmoil with them during the forty years of his administration. In 1709, three years after receiving the MA, Middleton joined other Fellows in a petition to John Moore, Bishop of Ely, as the College Visitor, against Bentley; but his marriage soon afterwards terminated his fellowship. It was not until 1717, after being created, among over thirty other scholars, Doctor of Divinity, by mandate, during George I's visit to Cambridge, that Middleton returned to the dispute with Bentley.

When Bentley, as Professor of Divinity, demanded that each of the new doctors pay him 4 guineas as a fee, many of them, including Middleton, were outraged and complied only on the condition that the money be returned if it was later determined to be an unjust assessment. But when Bentley still refused to return the money after being found to have acted unfairly Middleton began a suit against him in the vice-chancellor's court to recover his portion of the fee paid. Bentley's behaviour was so contemptuous of the University's authorities that finally, on 18 October 1718, he was stripped of his degrees and reduced to the extremity of petitioning the king for help in the dispute. At this point Middleton, among other complainants, thought it necessary to bring the scholars' grievances before the public. In 1719 he produced four pamphlets, the first of which, A full and impartial account of all the late proceedings in the University of Cambridge, against Dr. Bentley, reveals his early power as a controversialist:

The acrimonious and resentful feeling which prompted every line is in some measure disguised by the pleasing language, the harmony of the periods, and the vein of scholarship which enlivens the whole tract. Middleton's management of the subject is uncommonly artful. (Monk, 67)

After Arthur Ashley Sykes had entered the fray, in defence of Bentley, Middleton answered with yet more intense sarcasm. Since the pamphlets were anonymous Bentley chose to identify John Colbatch, a Fellow of Trinity and Middleton's friend, as the author of A True Account of the Present State of Trinity College, and when Bentley initiated a suit for libel Middleton published an advertisement (9 February 1720), declaring himself to be sole author of the piece. At this point Bentley prosecuted him in the court of king's bench, shrewdly leaping upon a passage in the pamphlet that seemed to reflect on the justice system of the country. Despite the upheaval in his College Bentley continued to pursue his scholarship and published proposals for an edition of the New Testament, which spurred Middleton to write yet another caustic attack on every paragraph of his enemy's pamphlet. Some contemporaries believed that Middleton's attack had quashed Bentley's plans, but Bentley's biographer regarded this claim as a commonplace error. Obviously seething with rage, Bentley replied so abusively—although against Colbatch rather than Middleton—that he was reprimanded by the Fellows. Nevertheless, in the long run the court of king's bench consistently favoured Bentley, and in 1724 forced the University to reinstate all the degrees that had been removed from him six years earlier by the senate.

In the end Middleton was compelled by Chief Justice Pratt to apologize to Bentley and to pay not only his own court costs but a portion of his adversary's, the total of which must have been enormous, since the College also paid £150 toward the expenses. But to ameliorate Middleton's humiliation and also to get even with Bentley the senate voted by a large majority, on 14 December 1721, to create a new position for him in the University Library, with the title ‘Protobibliothecarius’ and an annual income of £50, a position that he held to the end of his life.

In his new capacity Middleton again attacked Bentley, in 1723, on the pretext of his keeping some valuable manuscripts at his home, but the action once more invoked the wrath of the court of king's bench, and resulted in a £50 fine and a year's probation. Demoralized and in poor health, after being given leave of absence by the University Middleton departed for Rome in August 1723 and remained there until Easter 1724. Upon his return and the renewal of his law suit, in February 1726, he finally retrieved his 4 guineas from Bentley, with 12s. for costs.

The sojourn in Rome marked a crucial stage in Middleton's scholarly development. While there he enjoyed sumptuous hotel accommodation and spent lavishly on collecting antiquities, which he later described in print and sold in 1744 to Horace Walpole. However, the significant achievement of this immersion in classical culture was his Letter from Rome, published in 1729, which argued vigorously that many customs and rituals in the Roman Catholic church derived from ancient pagan religion. Though not an original view, as Middleton admits in the preface, the autobiographical form, anecdotal reference, and crisp style gave the work a personally authentic tone of an English protestant bemused at an exotic spectacle: ‘the whole form and outward dress of their worship seemed so grossly idolatrous and extravagant, beyond what I had imagined, and made so strong an impression on me, that I could not help considering it with a particular regard’.

Middleton argued that pagan rituals such as the use of incense, holy water, and lamps and wax candles were incorporated in the early Christian church; by ‘substituting their Saints in the place of the old Demigods’ the Catholics ‘have but set up Idols of their own’. Moreover just as the pagan Romans used a public whore to represent the goddess of liberty so Christian artists used their mistresses as models for pictures and sculptures of saints. He claimed that not only the Catholic priesthood but the office of the pope was based on pagan Rome's customs.

IAfter his first wife's death, in 1731, Middleton was named Woodwardian Professor of Geology, and gave lectures on the value of studying fossils to question the biblical account of the flood. On his second marriage, in 1734, he disqualified himself for this post and abandoned geology. By this time, however, he had gravely offended the church hierarchy by attacking one of its most respected members, Daniel Waterland. After Waterland's work Scripture Vindicated appeared in reply to Christianity as Old as the Creation (1730), by the deist Matthew Tindal, Middleton produced his anonymous Letter to Dr. Waterland (1731), which advised against trying to defend the historical accuracy of the Bible and advocated challenging Tindal's reliance on a ‘religion of nature’. To answer the deist Middleton argued that, since right reason was never found to be a sufficient guide, many heathens regarded this inadequacy ‘as the very cause of the invention and establishment of Religion’ (C. Middleton, Miscellaneous Works, 2.166).

Not surprisingly the argument that religion was ‘invented’ to compensate for the weakness of reason disturbed the Anglican orthodoxy; Zachary Pearce, later bishop of Rochester and dean of Westminster, issued Reply to a ‘Letter to Dr Waterland’, setting forth many falsehoods by which the letter-writer endeavours to weaken the authority of Moses (1731), which deplored Middleton's irreverence towards Moses as well as to Waterland. While quickly responding with A Defence of the Letter to Dr. Waterland (1731) and also with Some Further Remarks on a Reply to the Defence—in response to Pearce's Reply, which finally insinuated his infidelity—Middleton refused to retract anything: ‘Tis not my design to destroy or weaken any thing but those senseless systems and prejudices, which some stiff and cloudy Divines will needs fasten to the body of Religion, as necessary and essential to the support of it’ (C. Middleton, Miscellaneous Works, 2.182). When his authorship of this pamphlet became known Middleton came under attack from enemies at the university. In his reply to Pearce's second pamphlet, Some Further Remarks (1732), he clarified his argument still further and declared once again his sincerity as a Christian. Nevertheless, he was reproached for apostasy by the high-churchman Richard Venn. Furthermore an anonymous pamphlet by Philip Williams, public orator at Cambridge, demanded that the Letter to Dr. Waterland be burnt and the author banished unless he confessed his infidelity and formally recanted. In response Middleton reacted with his scornful Remarks on some Observations (1733):

Strange, that a man can be so silly as to imagine, that were I disposed to recant, I should not do it in my own words, rather than his! But I have nothing to recant on the occasion; nothing to confess. (C. Middleton, Miscellaneous Works, 2.315)

Though for some years thereafter Middleton avoided further theological controversy the damage to his standing within the church had been done, and he attributed the loss of a valuable friend, Edward Harley, second earl of Oxford, to the suspicion of his infidelity.

After the loss of Lord Oxford's friendship, in 1734 John Hervey, Baron Hervey of Ickworth, became Middleton's most congenial patron, for they shared an interest in music, classical studies, and rational theology. Hervey, as the great whig courtier in Robert Walpole's government, opened the way to great influence beyond the walls of Cambridge. Another patron, Thomas Townshend, MP for Cambridge University (1727-74), also gave Middleton valuable support by financing a biography of the great Roman philosopher and orator Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43BC).

Almost from the outset of their friendship Hervey was keenly interested in Middleton's plans to write a life of Cicero, and over the years continually cajoled or scolded him into completing the work. As their correspondence concerning the Roman senate reveals, Hervey may have also contributed significantly to the interpretation of Cicero's character. By August 1738 Middleton reported to him that a readable draft was finished and that it would be posted to him in sections for his perusal.

Throughout the body of his narrative Middleton portrayed Cicero ‘as a great Magistrate and Statesman, administering the affairs and directing the counsils [sic] of a mighty empire’ (C. Middleton, The History of the Life of Cicero, 3 vols., 1741, 1.157), and readers at the end of Walpole's long service in the government would readily see the historical parallel. As testimony to Cicero's political skill Middleton emphasized the Roman consul's deft manoeuvring to force Catiline into open rebellion against the state rather than play into the hands of ‘the whole faction [who] were prepared to raise a general clamour against him, by representing his administration as a Tyranny, and the plot as a forgery contrived to support it’ (ibid., 198). Equally praiseworthy in Middleton's view was Cicero's determination to stay independent of the powerful triumvirate formed by Crassus, Pompey, and Caesar. Cicero was particularly suspicious of Caesar's ambition to wrest total control of the republic. Though allowing for Cicero's depression and irresolute behaviour when events came to the crisis that forced him into exile Middleton stressed that it was on the advice of Cato and Hortensius that he fled Rome.

Middleton's Life of Cicero brought him substantial financial rewards and enabled him soon afterwards to purchase a ‘rude farm’ and turn it into an ‘elegant habitation’ where he enjoyed his summers; when Thomas Gray arrived at Cambridge in 1742 he regarded Middleton's house as ‘the only easy Place one could find to converse in’ (Gray). Despite the popularity of the biography it has been tainted since at least 1782, when Joseph Warton declared it to be a plagiarism of De tribus luminibus Romanorum (1634), by William Bellenden.

In 1741 the friendship between Middleton and Warburton came to an end over a disagreement about the former's claim that the Catholic religion derived from the ancient heathens. When, at the conclusion of the fourth book of The Divine Legation, in 1741, Warburton remarked that ‘many able Writers have employed their Time and Learning to prove Christian Rome to have borrowed their Superstitions from the Pagan City’, thus betraying ‘the grossest ignorance of human nature’ (Warburton, 4.356-7), Middleton took it as a personal attack and replied in a postscript to the fourth edition of A Letter from Rome, which appeared in the same year. Since Warburton had at first defended Middleton's Letter from Rome as well as his own Divine Legation from the accusations of heresy that William Webster published in the Weekly Miscellany perhaps he came to see his erstwhile friend as the uncompromising freethinker that he always was.

To his unsympathetic contemporaries Middleton's final years testified to the bitterness of an ambitious clergyman who had been passed over for preferment. After he had failed to win the post of master of the Charterhouse, even with Walpole's efforts on his behalf, the story goes that he was subsequently driven to attack anyone at all who tried to defend orthodoxy. As if to prepare the ground for a frontal barrage, in 1747 he launched first An Introductory Discourse to a Larger Work Concerning the Miraculous, which predictably stirred up his enemies. Then, two years later, he delivered his most relentless attack on the credibility of the church fathers, A Free Inquiry into the Miraculous Powers. In the spirit of John Locke, whose Third Letter on Toleration is evoked in the preface, Middleton argued eloquently against the testimonies of miracles given by patristic authorities and later writers. Without raising any heretical doubts about miracles in the apostolic period he boldly proclaimed his ‘honest and disinterested view, to free the minds of men from an inveterate imposture, which, through a long succession of ages, has disgraced the religion of the Gospel, and tyrannized over the reason and senses of the Christian world’ (C. Middleton, Miscellaneous Works, 1.xxiii). What especially alarmed Middleton's more orthodox Christian contemporaries was his exposé of the

quackery and imposture, as it was practised by the primitive wonder-workers; who, in the affair especially of casting out Devils, challenge all the world to come and see, with what a superiority of power they could chastise and drive those evil spirits out of the bodies of men, when no other Conjurers, Inchanters, or Exorcists, either among the Jews or the Gentiles, had been able to eject them. (ibid., 17)

Middleton's last published work, An examination of the lord bishop of London's discourses concerning the use and intent of prophecy, with a further inquiry into the Mosaic account of the Fall (1750), which dissected Sherlock's answer to the freethinker Anthony Collins, first published in 1725, seemed to provide final proof of the author's motivations: ‘spleen and personal enmity’ (Chalmers, 142).

When his health began to fail Middleton used his remaining years to answer two of his adversaries in a pamphlet published posthumously: A Vindication of the Free Inquiry from the Objections of Dr. Dodwell and Mr. Church (1751). For some reason, however, he chose not to answer his most formidable critic, John Wesley, whose Letter to Middleton (1749) stressed that without the ‘inner spirit’ and reliance on ‘internal evidence of Christianity’ the English people in a century or more would ‘be fairly divided into real Deists and real Christians’ (Wesley, 225). To judge by Middleton's ‘A preface to an intended answer to all the objections made against the free inquiry’, however, it seems unlikely that he was convinced by Wesley's stress on the inner light. In a letter to Hervey of 1733 he admitted that he was too much of a heathen to countenance the evangelical claims: ‘It is my misfortune to have had so early a taste of Pagan sense, as to make me very squeamish in my Christian studies’ (Chalmers, 145).

Middleton's endless quarrel with Bentley brought out a zest for attacking dogmatism in all quarters, so that in the end his formidable power as a writer was largely negative. In 1736 he wrote to Warburton:

As for myself, I can safely swear with Tully, that I have a most ardent Desire to find out the Truth: But as I have generally been disappointed in my Enquiries, and more successful in finding what is false than what is true, so I begin, like him too, to grow a mere Academic [sceptic], humbly content to take up with the probable. (C. Middleton, Miscellaneous Works, 2.467)

His success in finding out the ‘false’ helped to change the course of theological debate in his own period and afterwards. Modern scholars have recognized his importance to the rise of ‘higher criticism’ of the Bible (Stromberg, 78). This disposition proved useful for non-theological controversies as well. Against the popular notion at the time that William Caxton had been preceded by a printer at Oxford, Middleton published A Dissertation Concerning the Origin of Printing in England (1734-5), which argued vigorously that Caxton had introduced the printing press to England.

Middleton died in Hildersham, Cambridgeshire, on 28 July 1750, ‘of a slow hectic fever and disorder in his liver’. He was buried in the parish of St Michael, Cambridge, on 31 July. His biography of Cicero was a benchmark in what has been called ‘the rise of modern paganism’ (Gay, title-page). Passing through nine editions within the eighteenth century and numerous other editions and reprints in the nineteenth century, it was his most enduring literary achievement. Probably a large part of its appeal derives from its providing an ideal of good citizenship and political independence for aspirants in the British parliamentary system.

DNB

Conyers MiddletonShield located above the stalls on the south side of the Chapel |

|

|

|

PREVIOUS SHIELD |

|

NEXT SHIELD Edmund Miller |

| Shield Gallery | Sculpture Gallery |

Brass Gallery | Statue Gallery | Interment &Tombstone Gallery | War Memorial Gallery |