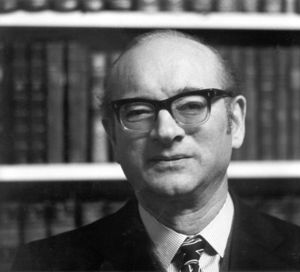

Ralph Alexander Leigh

1915-87.  Fellow, Professor of French Literature.

Fellow, Professor of French Literature.

Leigh was born in Poplar, Tower Hamlets, London, the son of a journeyman tailor. His mother died tragically when he was nine. He won a scholarship to Raines' Foundation School for Boys and then won Drapers' Company and London county council scholarships to study French at Queen Mary College, London University, graduating BA with first-class honours in 1936. A Clothworkers' Company scholarship enabled him to continue his studies at the University of Paris from 1937 to 1939. During the Second World War he served with the Royal Army Service Corps, reaching the rank of major in 1944; he was posted to Berlin during 1945-6. In 1945 he married the pianist Edith Kern, whom he had met at the Sorbonne in 1938.

In 1946 Leigh was appointed lecturer in French at the University of Edinburgh. The basis of his remarkable book collection, now in Cambridge University Library, was laid in that city. In 1952 he moved to Cambridge as a university lecturer in French; he became university reader in 1969 and held a personal professorship of French from 1973 until his retirement in 1982. He was also in 1952 elected a fellow of Trinity, where he was Praelector for many years and a remarkable teacher. He was elected FBA in 1969 and was appointed CBE in 1977 and chevalier of the Légion d'honneur in 1979 (he was to have been made officier in 1988). He held honorary doctorates at the universities of Neuchâtel, Geneva, and Edinburgh, and was due in 1988 to be honoured at Oxford.

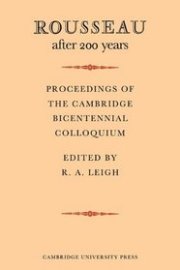

Leigh was the sole editor of one of the great scholarly achievements of the twentieth century, the Correspondance complète de Jean-Jacques Rousseau (53 vols., 1965-98). His choice of Rousseau for so much intent and inventive attention was made early, and was neither light nor accidental. While a student, he had discovered, with an irritation that never left him, the shortcomings in erudition and intellect of the previous edition. The brilliant outsider (born in Geneva, not France) whose arguments for justice and freedom were sharpened by a sense of exclusion and laced by derision, whose work had been misinterpreted and even deformed, who was hypersensitive and persecuted, evoked resonances in the young scholar of the 1930s, himself born into a poor East End Jewish family.

Leigh was the sole editor of one of the great scholarly achievements of the twentieth century, the Correspondance complète de Jean-Jacques Rousseau (53 vols., 1965-98). His choice of Rousseau for so much intent and inventive attention was made early, and was neither light nor accidental. While a student, he had discovered, with an irritation that never left him, the shortcomings in erudition and intellect of the previous edition. The brilliant outsider (born in Geneva, not France) whose arguments for justice and freedom were sharpened by a sense of exclusion and laced by derision, whose work had been misinterpreted and even deformed, who was hypersensitive and persecuted, evoked resonances in the young scholar of the 1930s, himself born into a poor East End Jewish family.

Leigh's work goes far beyond what is usually expected in an edition of the letters even of a great thinker and complex personality such as Rousseau. It contains far more letters than were recorded in previous collections and editions. It is based not on a printed tradition but on collation of the actual manuscript where it still exists. It gives variants and different versions of letters systematically and not sporadically. These versions are particularly important in the case of Rousseau because they illuminate cruxes in Rousseau's thought or in the course of his reaction to events in his life (for instance, the letter on Providence to Voltaire, 18 August 1765, where the complex changes traced may shed crucial light on Rousseau's evolving anti-materialism). Leigh identified and tracked down the lives of several thousand persons mentioned in the letters; where relevant he printed the letter to which Rousseau replied or the reply it evoked. Even more strikingly, he continued the collection beyond the date of his subject's death, so that the vexed question of Rousseau's influence on the French Revolution receives illumination from the papers. In the last volumes of his edition, Leigh published letters of reaction to Rousseau's death, but also accounts from the press, from memoirs, and from ephemera, which amount to a vast canvas of Rousseau's posthumous presence in France. It has become apparent after Leigh's own death that the edition has laid down a new set of measures and expectations about what such an enterprise, so conducted, can contribute to a community's knowledge; in this case, the community reaching out well beyond a group of the learned and scholars of the period that it might first seem to have addressed. The edition has become a standard work of reference for material beyond Rousseau, and has been placed on the open shelves of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. This makes of it an emblem of its message: the intellectual, and not merely scholarly, importance of the detail of the field from which the great work arises.

Tall, short-sighted, and gangling, Leigh was an eloquent and witty debater whose urbanity would turn to passion and fury in the face of suffering and injustice. He loved music and wrote poetry, and his formidable intelligence engaged in whatever his eyes sparkling behind his glasses turned to consider. His enjoyment of the Johnson Club, as of the peculiarities of life within a Cambridge college (where he lived after the death of his wife in 1972), and of social and academic success was real enough. But these never outweighed the delight in scholarship, the keener if it were sharp and polemical, or the utter respect for intellectual achievement that he lived by. He died in Cambridge and was buried in Trumpington cemetery. © DNB

| Memorial inscription | Translation |

|

RALPH ALEXANDER LEIGH LECTOR PRAELECTOR PER XXXVI ANNOS SOCIVS |

Ralph Alexander leigh was Lecturer, Praelector, and for thirty-six years Fellow of the College, and Professor of French Literature in the University. A man pre-eminent in intellect, eloquence and erudition, he compiled a learned stock of annotations to the collected correspondence of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, bringing to that obscure mind his own enlightenment. He died suddenly at the age of seventy-two in 1987, just as he was about to put the finishing touches to this massive work. |

Ralph Alexander LeighBrass located on the north wall of the Ante-Chapel. |

|

|

|

PREVIOUS BRASS |

|

NEXT BRASS Gerald Ponsonby Lenox-Conyngham |

| Brasses A-B | Brasses C-G | Brasses H-K | Brasses L-P | Brasses R-S | Brasses T-W |