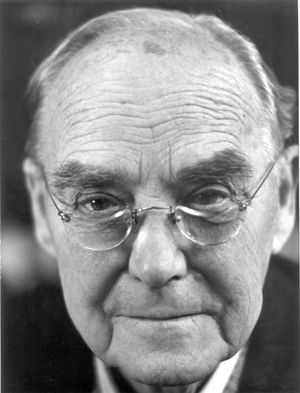

Sir Geoffrey Ingram Taylor, OM

1886-1975. Meteorologist. Yarrow Research Professor to Royal Society.

1886-1975. Meteorologist. Yarrow Research Professor to Royal Society.

Taylor was the grandson of George Boole, the inventor of Boolean logic. As a child Geoffrey was fascinated by the Royal Institution's Christmas lectures, which set him on the path to a career in physics. He read Mathematics and then, on a major scholarship, Natural Sciences at Trinity, and was then awarded a prize fellowship, enabling him to stay on in the Cavendish Laboratory.

In 1911 he was appointed Reader in Dynamical Meteorology, and in 1915 won the Adams Prize for his work on atmospheric turbulence.

In 1913 Taylor served as a meteorologist aboard the Ice Patrol vessel Scotia, where his observations formed the basis of his later work on a theoretical model of turbulent mixing of the air. At the outbreak of World War I, he was sent to the Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough to apply his knowledge to aircraft design, working, amongst other things, on the stress on propeller shafts. Not content to simply sit back and do the science, he also learned to fly aeroplanes and make parachute jumps.

After the war Taylor returned to Trinity and worked on an application of turbulent flow to oceanography. He also worked on the problem of bodies passing through a rotating fluid. In 1923 he was appointed to a Royal Society research professorship as a Yarrow Research Professor. This enabled him to stop teaching which he had been doing for the previous four years and which he both disliked and had no great aptitude for. It was in this period that he did his most wide-ranging work on the mechanics of fluids and solids including research on the deformation of crystalline materials which followed from his war work at Farnborough. He also produced another major contribution to turbulent flow, where he introduced a new approach through a statistical study of velocity fluctuations.

In 1934, Taylor, roughly contemporarily with Michael Polanyi and Egon Orowan, realised that the plastic deformation of ductile materials could be explained in terms of the theory of dislocations developed by Vito Volterra in 1905. The insight was critical in developing the modern science of solid mechanics.

During World War II Taylor again worked on applications of his expertise to military problems such as the propagation of blast waves, studying both waves in air and underwater explosions. These skills were put to the service of scientists at Los Alamos when Taylor was sent to the United States as part of the British delegation to the Manhattan project between 1944 and 1945. In 1944 he also received his knighthood and the Copley Medal from the Royal Society.

Taylor continued his research after the end of the War serving on the Aeronautical Research Committee and working on the development of supersonic aircraft. Though officially retiring in 1952 he continued researching for the next twenty years, concentrating on problems that could be attacked using simple equipment. This led to such advances as a method for measuring the second coefficient of viscosity. Taylor devised an incompressible liquid with separated gas bubbles suspended in it. The dissipation of the gas in the liquid during expansion was a consequence of the shear viscosity of the liquid. Thus the bulk viscosity could easily be calculated. Other late work included the longitudinal dispersion in flow in tubes, movement through porous surfaces and the dynamics of sheets of liquids.

Aspects of Taylor's life often found expression in his work; his overriding interest in the movement of air and water, and by extension his studies of the movement of unicellular marine creatures and the weather, were related to his lifelong love of sailing. In the 1930s he invented the 'CQR' anchor which was both stronger and more manageable than any in use and which was used for all sorts of small craft including seaplanes.

In his final research paper, published when he was 83, he resumed his interest in electrical activity in thunderstorms, as jets of conducting liquid motivated by electrical fields. The cone from which such jets are observed is called the Taylor cone in his honour.

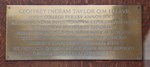

| Memorial inscription | Translation |

|

GEOFFREY INGRAM TAYLOR O.M. EQ. AVR. HVIVS COLLEGII PER LXV ANNOS SOCIVS |

Sir Geoffrey Ingram Taylor, O.M., was a Fellow of the College for sixty-four years. By nature suited to inquiry, investigation and experiment, he explored many different branches of physics. With his remarkable ability in mathematics he was able to solve problems of all kinds. He was free from all artifice and friendly towards everyone. Even at an advanced age his intellectual power was undiminished. He died in 1975 at the age of eighty-nine. |

Geoffrey Ingram TaylorBrass located on the north wall of the Ante-Chapel. |

|

|

|

PREVIOUS BRASS |

|

NEXT BRASS Sedley Taylor |

| Brasses A-B | Brasses C-G | Brasses H-K | Brasses L-P | Brasses R-S | Brasses T-W |